The decorative stones of St Andrew’s Church, Dent

View more articles about the History of the Churches of the Western Dales

The text below is taken from a church booklet written by William Fraser, Hon. Secretary of the Leeds Geological Association. It is reproduced with kind permission of the author.

The original Church was built in the 12th century then rebuilt in 1417, following which it underwent restorations in 1590, 1787 and 1889. Fortunately, Dentdale is well provided with building stones so local rocks have been used for most of the work. These were deposited between 330-325 million years ago during the Carboniferous Period when Dentdale was a very different to what it is today. Then it was part of a shallow tropical sea into which rivers were washing vast amounts of sediment that was deposited as deltas which built out into, and on occasions, filled it. Periodically sea levels rose rapidly, flooding the deltas with open seas before they were gradually rebuilt. In the open sea conditions marine life thrived and shell debris accumulated on the seabed. As deltas advanced mud was deposited on top of this, then sands as the waters shallowed. Over time the layers of sediments became compacted and cemented, turning them into the beds of limestone, shale and sandstone which are the rocks that were dug from many small quarries on the surrounding hillsides.

The Chancel Floor

While the walls of the Church are built of limestone and sandstone, it is the floor of the chancel and altar, which was probably added in the 1889 restoration, that are most interesting as several different types of limestone have been used. While these are referred to as 'marbles' they are not true marbles but simply limestones that can be polished. True marble requires limestone to have been re-crystallised by heat and/or pressure, which these haven't. This makes them no less inferior as a product as the original features of the rock are very attractive. Two of the limestones are examples of Dent Marble the production of which was an important local industry for over 300 years.

“[Dent] is in a dale which abounds with veins of black and grey marble, of superior quality and great beauty. Considerable quantities of this article are sent to London and many other parts of the kingdom; and there are extensive works here for the finishing and polishing the marble, upon new and improved principles” (Slater & Co 1848, 63).

Polishing limestone was carried out in Dentdale as a cottage industry from around the early C17th but in the early C18th a watermill at Stonehouse in upper Dentdale was converted to cut and polish it on an industrial scale. Seven different limestone formations occur in Dentdale and adjoining dales but only four were found to be suitable: the two lowest in the rock sequence, and the two highest. Stone was quarried from small quarries in the area and taken to Stonehouse where it was cut and polished and made into fireplaces, floor tiles, chessboards and other decorative objects. The products were used locally as well as being widely exported across the country and overseas, including one piece to the Czar of Russia's Winter Palace in St Petersburg.

Black Marble – Dent

The two lower limestones in the Dent area found suitable for polishing are the Hardraw Scar and Simonstone Limestones. Both are very dark in colour, fine- grained and, when polished, produce a jet-black rock called the ‘Black Marble’. Any fossils in the rock were regarded as blemishes and the slab would have been discarded.

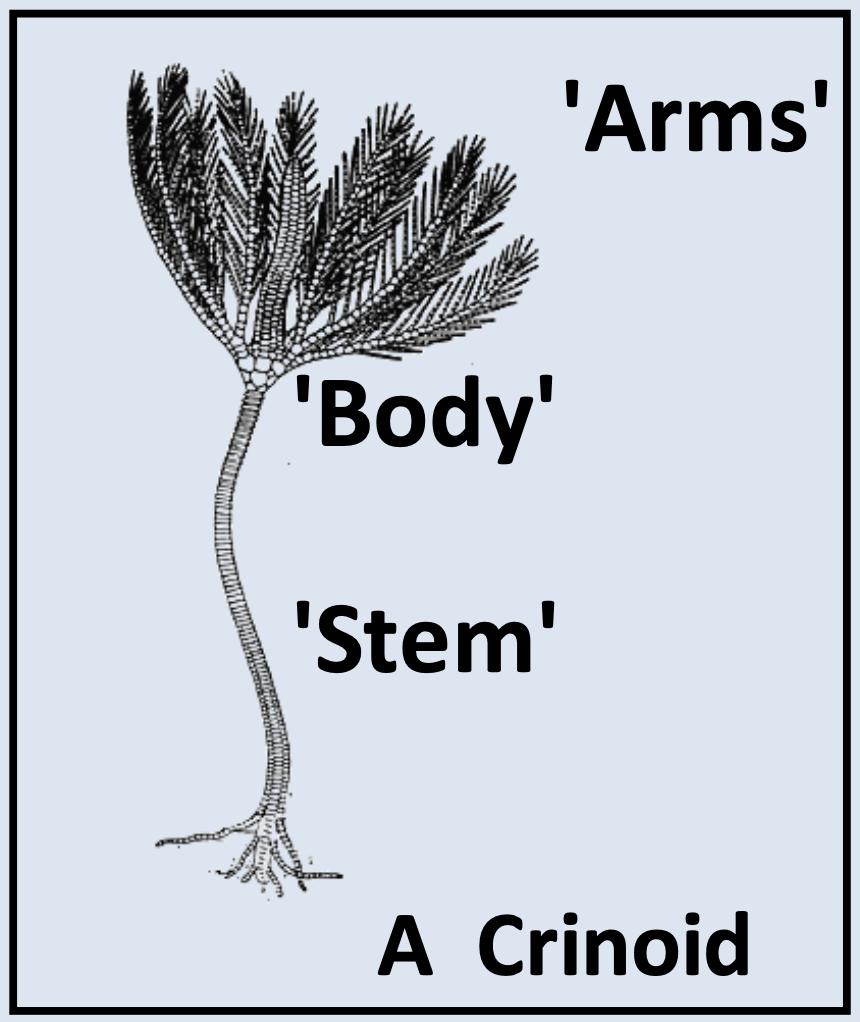

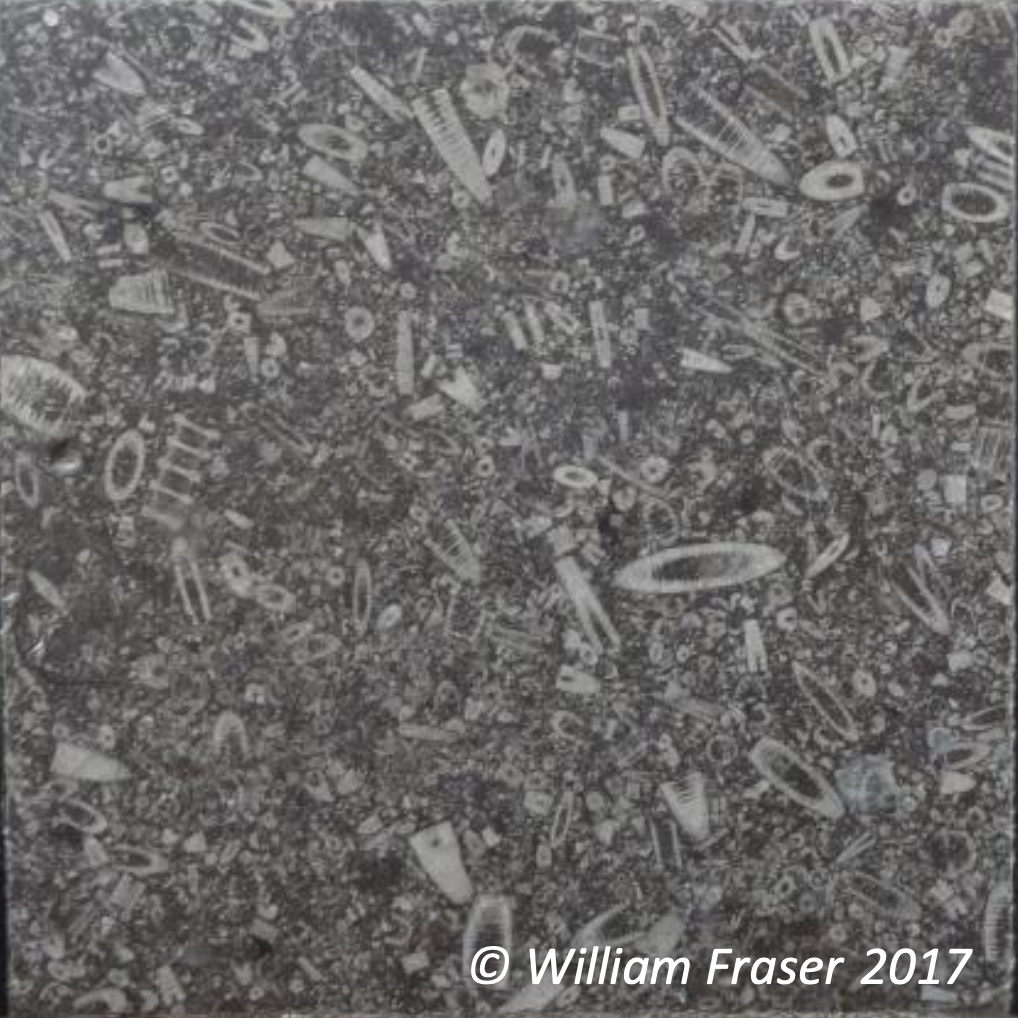

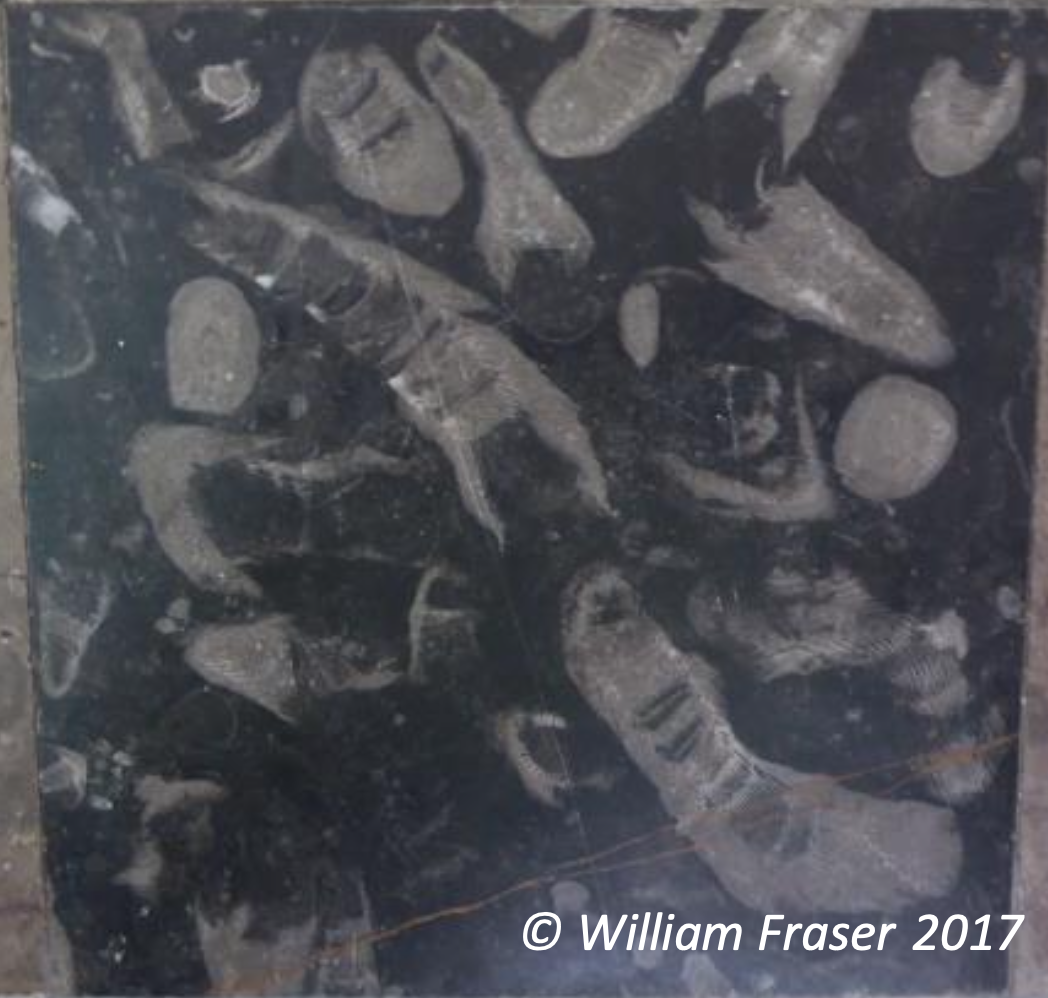

The two higher limestones, the Underset and the Main Limestones, are both grey in colour but crammed with the fossilised remains of shellfish called crinoids. These had a skeleton made of many individual calcareous 'plates'. The ‘body' and food collecting ‘arms’ of the animal were supported above the seabed by a 'stem' made of many discs (ossicles), each with a hole in the middle, that could be several 10's of cm long. During life the skeleton was covered by a thin skin but when the animal died this quickly decayed and the skeleton collapsed onto the seabed in pieces. Sections through the stems are the most obvious feature in the polished surfaces; the different angle that they lay on the seabed giving them their different appearances when cut. (often mistaken for jaws!)

Fossil Marble – Dent

For periods of time the conditions must have been just right for crinoids to thrive in vast numbers and the sea floor was covered in forests of them. This allowed thick accumulations of their remains to build up and to eventually become turned into rock. Now, cut and polished, this forms the Fossil Marble in which the white crinoid stems make striking patterns in the pale grey rock. When used alongside the Black Marble as in the chancel, it creates a chessboard appearance.

Barrow Marble – Ulverston

Forming a border to the Dent Marbles in the chancel, and on the altar floor, is a mottled brown stone. Known here as the Barrow Marble it is probably one that also goes by the name Ulverston Brown or Oatmeal Marble. It is also the rock that the Font is carved from and is another polished limestone, of similar age to the Dent Marbles but it came from quarries around Barrow-in-Furness.

Frosterly Marble – Weardale

The altar floor, as well as being paved with tiles of the Black, Fossil and Barrow Marble, has another polished limestone from the north of England; the Frosterley Marble from Weardale, Co. Durham. This black rock contains large fossil corals whose delicate internal structures form intricate patterns in the polished surfaces. It appears in many churches across the north of England, Durham Cathedral has columns and floor tiles made of it, and further afield - even as far as Mumbai in India!

True marbles – overseas

Around the altar the floor is paved with a mixture of reddish and white tiles. These are true marbles, so not local but imported from overseas.